Armistead, B.

Birth

Death

First Name

Last Name

Person Title

PersonID

Note

Name in Index

Person Biography

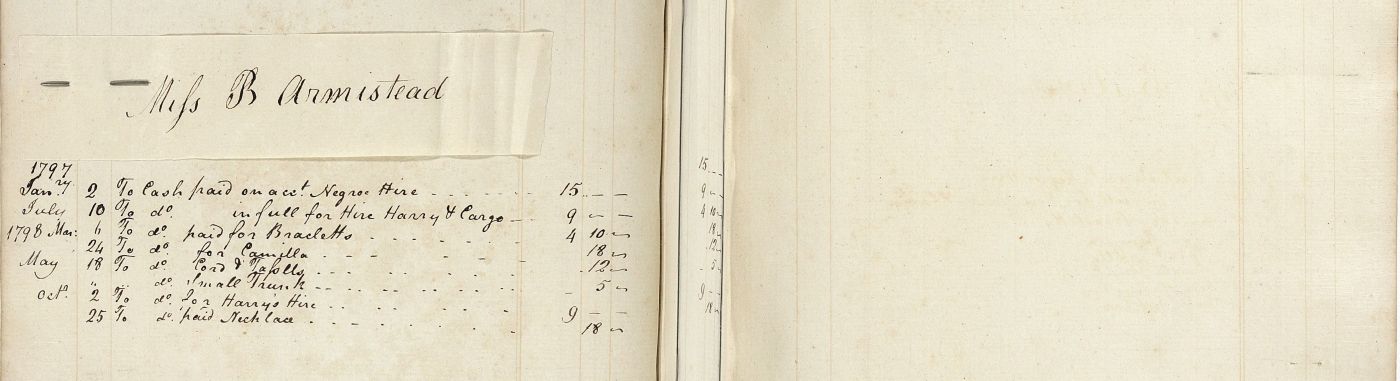

Mary Bowles Armistead—the most likely candidate for the “Miss B. Armistead” listed in the Mason family manuscript account book—was born to Bowles Armistead and Mary Ann Fontaine Armistead in 1783 in Hanover, Virginia. As a member of a large and wealthy Virginia family, Mary Bowles was embedded in an interconnected network of elite relationships throughout her entire life. After Mary Bowles’s father died in 1785 when she was barely two years old, her mother married Colonel John Lewis, son of Fielding Lewis and stepson of George Washington’s sister, Betty Washington Lewis. Since children typically remained with their mothers following remarriage in the late eighteenth century, it is likely that Mary Bowles grew up in Fredericksburg, where her stepfather John assisted Betty in managing the family’s plantation at Kenmore until Betty’s death in 1797.

Mary Bowles Armistead did not inherit any land from her father that would have given her occasion to live in Loudoun County between 1797 and 1798, but evidence suggests that she may have frequently visited the county during this period. Like their mother had done when she married an Armistead, Mary Bowles’s sister Elizabeth Armistead joined a powerful and well-connected family when she married Richard Henry Lee’s son Ludwell Lee in 1797. That same year, Mary Bowles’s stepfather sold Kenmore and prepared to move to Kentucky, which may have encouraged the unmarried Mary Bowles to spend periods of time visiting or living with her sister and brother-in-law in Alexandria (their primary residence until 1799). The trio visited their neighbor, George Washington, several times at Mount Vernon between 1797 and 1798—the same period that “Miss B. Armistead” appears in the Mason family manuscript account book. Since Ludwell had inherited land in Loudoun by 1797 from both his first wife, Flora Ludwell Lee, and his uncle, Francis Lightfoot Lee, it is likely that Mary Bowles accompanied her sister and brother-in-law on trips to the county as Ludwell began managing the land and preparing for the construction of his future home at Belmont Plantation.

While Mary Bowles Armistead’s entry in the Mason family manuscript account book is brief, it offers an illuminating window into elite women’s material culture and participation in Virginia’s slave society. Her purchases of jewelry, fabric adornments, and a small trunk to hold her possessions was typical for a teenage girl with an eye for fashion approaching a marriageable age. However, the reasons behind her recurrent hiring of enslaved laborers are harder to discern. As an upper-class southern white woman who had inherited enslaved laborers from her father, Mary Bowles was well-versed from girlhood onward in the practice of managing enslaved individuals. These experiences prepared her for her work as a wife running farming estates: first at Alexandria’s Mount Ida, where she lived with her first husband, Charles Alexander, whom she married in 1800; then at Loudoun County’s Exeter, where she lived with her second husband, Wilson Cary Selden, after they married in 1817.

Mary Bowles had six children with Alexander and three with Selden. Written just a year before her death in 1846, one of her few surviving letters is addressed to her granddaughter Eleanor Love Selden, who married John Augustine Washington III, the great-grand nephew of George Washington and the last private owner of Mount Vernon. In it, she apologized for not being able to loan Eleanor an enslaved “stacker” for bundling and storing wheat—demonstrating the extent to which elite women like Mary Bowles relied upon and perpetuated the slave society in which she lived.

By Nicole Penn