Littleton, Sampson

Birth

Death

First Name

Last Name

PersonID

Name in Index

Person Biography

Sampson Littleton was born around 1758 to William and Mary Littleton in Dorchester County, Maryland, and grew up with six brothers. Littleton married Kelly “Kitty” Cockrell in December 1799, with her father Joseph Marmaduke Cockrell serving as witness. Tax records from 1800 suggest that the newlywed Littletons may have been living with Sampson’s brother, Solomon. Both men were living in District Two of Loudoun County and were listed next to one another on the personal property tax lists, but only one brother was taxed. Sampson had no taxable property that year, but Solomon was charged $56 for one “Black under 12,” presumably an enslaved child, and one horse. Owning or renting enslaved people was a marker of at least some wealth and financial success. While clearly not elite or independently wealthy, the Littletons did not belong to the poorest class of white Virginians.

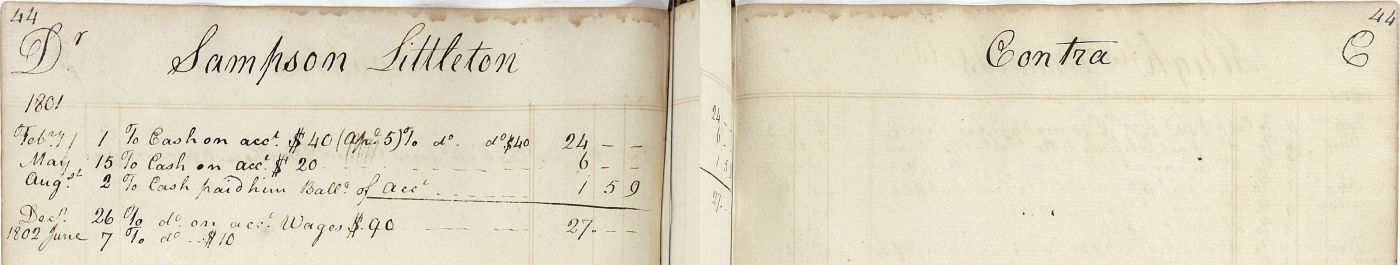

Sampson Littleton worked for Stevens Thomson Mason in several capacities at Raspberry Plain between 1797 and 1804, including as an overseer. Following Mason’s death, executors of his will appraised the plantation estate and over the following year settled his debts. Littleton is listed several times in this record, where executor John T. Mason recorded payments over time for things owed him such as “harvest wages” and “wages as overseer.” Payments ranged from $12.73 to $456.50, indicating his lengthy employment, his importance to plantation success as an overseer, and the prosperity of the plantation itself.

Plantation overseers were typically lower- or middle-class men who had experience working in agriculture or a trade. Though their skills and knowledge were undoubtedly useful in their employment, their major responsibility was to manage the enslaved laborers on the plantation. This management would have included the direction and supervision of tasks and often violence against enslaved people. Slaveholders and their employees leveraged violence as punishment and as a tool to increase profits through fear and physical torment. During his time at the Masons’ Raspberry Plain plantation, Littleton received his wages in cash.

In 1810, slightly more than ten years after their marriage, Sampson and Kitty Littleton were still living in Loudoun County and appear to have had four children. The census of that year indicates that in the Littleton household there was one adult white man, one adult white woman, and four free white children, two boys and two girls. Sampson and Kitty eventually had a total of five children.

What ultimately became of Littleton is unknown. He did not file a will in Loudoun County, so it is possible that he either died without a will or that he and his family moved elsewhere. It is also possible that Littleton lost his life in military service during the War of 1812, as he, like every other able-bodied man in Loudoun County, served in the 56th and 57th militia regiments.

The next generation of Littletons scattered beyond Loudoun County. It was not uncommon for Virginians to move westward during this period, and at least two of Littleton’s children moved to Ohio. His daughter Nancy was still in Loudoun when she married a man named Abel Marks in 1824 and when she gave birth to her son Andrew, but by 1830 that branch of the family had moved west. The 1830 census recorded Abel Marks and his family of five—including a white woman over twenty and four white children—living in Moorefield, Ohio, a community in Clark County near Springfield. This portion of the family remained in Ohio, as the death record of their first son, Andrew, in 1908 was filed in Columbus, Ohio. In 1838, Littleton’s son Lorenzo married a woman named Sidney Norman in Madison, Ohio, and is later documented on the 1840 census living in Pickaway County, Ohio, just south of Columbus. It is unclear whether all of Littleton’s children made the journey westward, but based on the roots planted in Ohio by Lorenzo and Nancy, it is possible that Sampson and his wife Kitty followed them to live out their later years.

By Annabelle Spencer