, Phillis

Birth

Death

First Name

Person Biography

Phillis was an enslaved woman who along with her mother and seven siblings was held in bondage by Armistead T. Mason as part of a trust he managed on behalf of his younger cousins Elizabeth and Mary Armistead. Their father, Robert Armistead, organized this trust in 1805, having inherited Phillis and the other members of her family following the 1804 death of his first wife, Lucinda Margaret Ellzey Armistead. It is likely that Lucinda had in turn received Phillis’s mother, Esther (or Hester), and a few (if not all) of Esther’s children as a gift from her own mother, Alice Blackburn Ellzey, in 1796.

Phillis’s line of ownership illustrates how elite women benefited from and perpetuated Virginia’s system of slavery. Upon his death in 1796, Lucinda’s father, Loudoun County landowner William Ellzey, directed in his will that his wife Alice receive “all my slaves to be disposed of in her lifetime or at her death among my children as she shall think proper.” Alice renounced the widow’s inheritance that she had received from William that same year, possibly as she was expecting to live with and be cared for by one of her other family members and did not want to be burdened with the complexities of managing her husband’s estate. Although neither Phillis nor her mother were explicitly mentioned in William’s will, they represented a valuable source of independent and portable wealth for Alice’s daughter Lucinda (and eventually Lucinda’s daughters, Elizabeth and Mary Armistead), particularly on account of the reproductive labor they could provide as women. Slaveholders valued enslaved women for their potential to increase their owners’ property by giving birth to enslaved children.

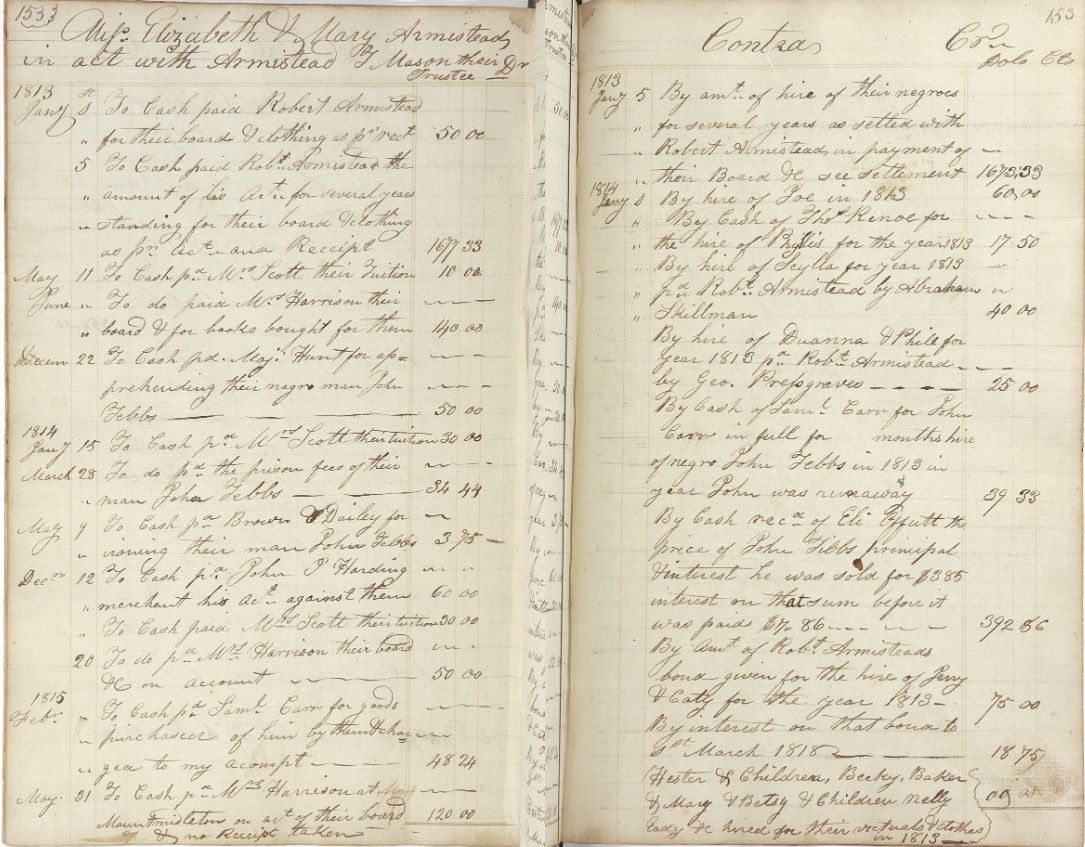

It is unclear precisely when or where Phillis was born, when or where she died, or if she ever married or had any children. Even so, details from the Mason family manuscript account book illustrate that her life was in many ways typical for an enslaved laborer in Loudoun County. Armistead T. Mason hired Phillis out annually to earn money for Elizabeth and Mary Armistead between 1813 and 1817. Phillis earned $17.50 for her owners in 1813 after being hired by Thomas Renoe, who worked for Armistead’s mother, Mary Mason; and $20 in 1814, 1815, and 1816 after being hired by Armistead’s overseer John Huff. Loudoun landowner John Newton also hired Phillis for the year in 1817, earning the Armistead girls $25. It is likely that all three renters hired Phillis as a field worker, using her to grow the wheat, corn, and rye that formed the backbone of Loudoun County’s farming economy in the early nineteenth century. Phillis likely worked from sunrise to sundown six days a week ploughing fields and sowing seeds for wheat and rye between August and November, harvesting and storing corn in December and January, resuming the planting cycle again for corn between February and May, and concluding the agricultural calendar in June and July with the difficult labor of reaping and threshing the wheat and rye that she and other enslaved laborers planted the previous fall.

Armistead T. Mason was able to steadily increase the price he charged to hire Phillis out over four years, a testament to the value her labor commanded as she reached her most productive age, especially in the decade following the outlawing of the transatlantic American slave trade in 1808. The end of the Atlantic trade turned enslaved laborers into one of Virginia’s most valuable exports, siphoning much of Virginia’s labor force further south. The exodus of enslaved workers from the state’s northern counties was especially heavy. Phillis was not hired out in 1818, although Mason used her to send money to David Dyas in July, who appears to have been another one of his overseers or workmen. She was not mentioned in Mason’s will, nor in the inventory list compiled following his death in 1819.

The demand for enslaved laborers to service the growing cotton plantations of the Deep South, coupled with the fact that Elizabeth and Mary Armistead were nearing marriageable ages, likely encouraged Mason to sell Phillis by the end of 1818. Having lost her mother, Esther, and her sister, Scylla, to death just a few years prior, Phillis may have further endured the pain and trauma of being permanently separated from the rest of her siblings who remained in Loudoun for the sake of securing Elizabeth and Mary Armistead’s financial futures.

By Nicole Penn