Hopkins, Betsy

Birth

Death

First Name

Last Name

Name in Index

Person Biography

Elizabeth “Betsy” Binns Hopkins was a free woman of color and a seamstress active in Loudoun County in the nineteenth century. Archival records indicate that Betsy was likely born in 1791. It is unclear where she was born, but documents show that she was enslaved by Simon Alexander Binns, brother of farmer and agricultural innovator John Binns of Clover Hill Plantation in Waterford. The Binns family was well known in Northern Virginia and had accounts with the Masons. On 24 February 1811, Elizabeth Binns married an enslaved man named Harry Hopkins in Loudoun County. Betsy was manumitted and became a free woman in 1824. Harry was freed sometime before 1851, when he first appears on Loudoun County’s “List of Free Negroes.”

In 1827, Betsy Hopkins was tried by the Commonwealth of Virginia for remaining in the state contrary to law. In 1806, the Commonwealth enacted a law that stated that if an emancipated formerly enslaved person stayed in the Commonwealth for more than one year after being granted their freedom, that person “shall forfeit all such right, and may be apprehended and sold by the overseers of the poor of any county or corporation in which he or she shall be found, for the benefit of the poor of such county or corporation.” Many formerly enslaved Virginians were sent to court for breaking this law; leaving one’s home for a new state was not possible for every freed person, due to the cost of travel, familial connections in Virginia, and other complications. Many freedpeople simply evaded the law and stayed put.

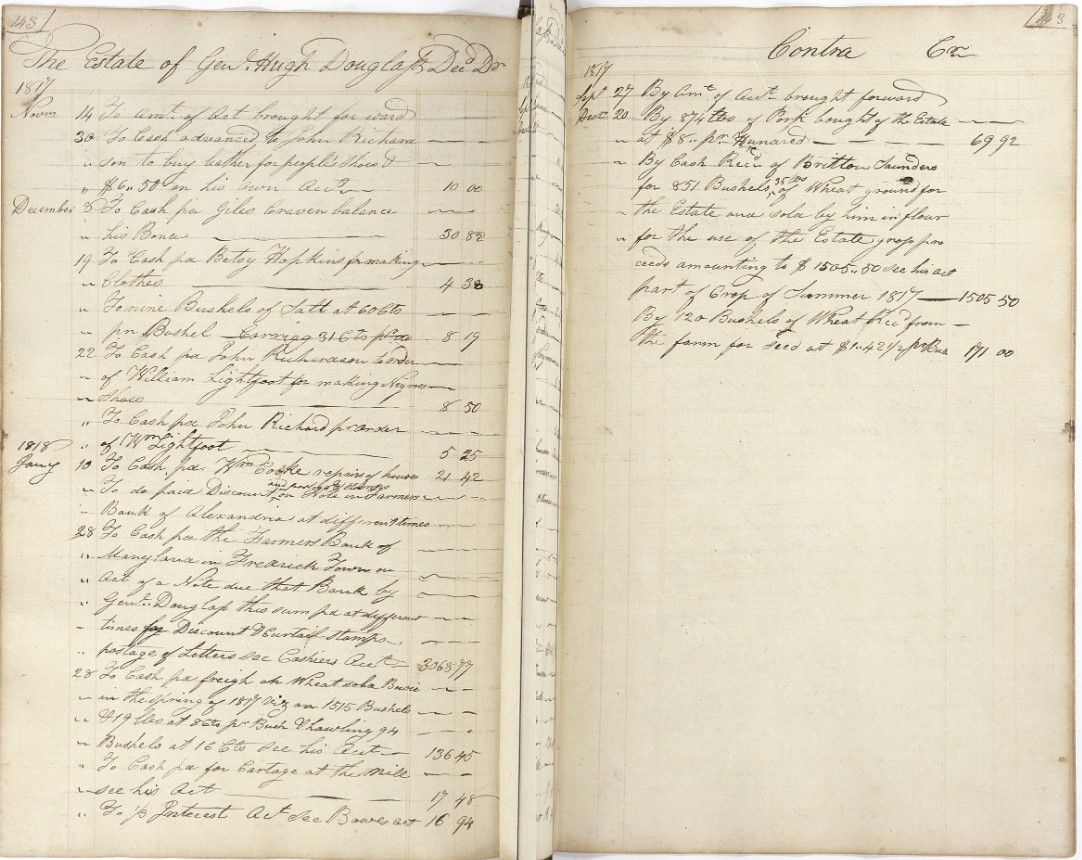

On 19 December 1817, Hopkins was paid $4.30 out of Hugh Douglas’s estate account for making clothes. Historian Gloria Seaman Allen states that seamstresses played an invaluable role within plantation society, and argues that enslaved seamstresses were “in the best position of any enslaved textile artisan in the Chesapeake region to continue [their] trade when freedom came.” It seems this was true for Hopkins, who continued to work in domestic labor roles—included washing clothes and performing housework—after gaining her freedom.

Hopkins’s age at the time of her death remains uncertain. An article from the 27 February 1880 edition of the Staunton Vindicator stated:

"The colored people in Virginia, instead of dying out, are in a fair way to get the prize for long life. Betsy Hopkins, colored, of Waterford, Loudon county, has just ended a life of one hundred and six years duration."

While this article indicates that she would have been born in 1774, it is unclear where the author found his evidence. Hopkins’s death certificate states that she died on 10 May 1880 of old age in Waterford at the age of ninety-four, which would make her birth year 1786; all other documentation suggests that she was eighty-nine at the time of her death. Her husband Harry’s death date is unknown.

By Jayme Kurland