, Ajacks

Birth

Death

First Name

Person Biography

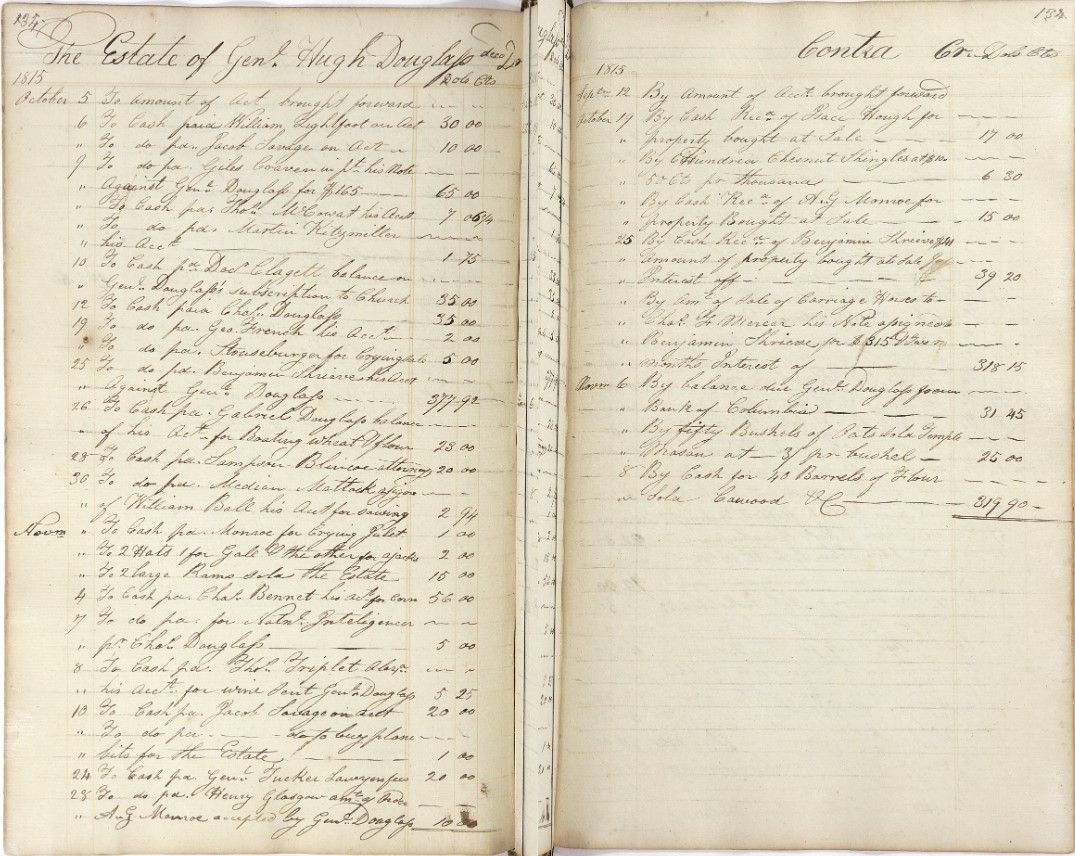

Ajacks or Ajack was an enslaved man held by Hugh Douglas, a Loudoun County plantation owner. References to him appear in two folios in the Mason family manuscript account book, as well as in the accounts of the Douglas estate. In his will, Douglas advised that his property, including human property, be sold if necessary to provide for the “education…and expenses” of his children. Armistead T. Mason, as executor of Douglas’s estate, was in charge of carrying out the terms of his will. In 1816, the year after his death, the Mason and Douglas accounts list expenses owed to Richard Williams, the Masons’ formerly enslaved overseer, who arranged the sale of Ajacks and another enslaved man, Isaac.

Before being sold, Ajacks probably lived in a comparatively large enslaved community at Douglas Bottoms, where thirty-four people were held in bondage according to the 1810 census. Of that group, Ajacks and Isaac appear to be the only ones sold off initially by the Douglas estate. Isaac had previously run away and been returned, so he may have been viewed as a liability. Beyond that, it is unclear if there were any particular reasons why he or Ajacks were sold, or to whom and where they were sold.

Aside from the references to him in these account books, there appears to be no trace of this particular Ajacks—or any other spelling variant of his name—in the historical record. Other enslaved men with his name, more commonly spelled to reference the Greek mythological hero Ajax, appear sporadically throughout the South in this period. This use of the name Ajax was part of a larger trend of giving enslaved people classically inspired names, a trend that sheds light both on how slaveholders saw their human property and how enslaved people created their own traditions and community. Slaveholders often gave new names to the people they enslaved. Names like Caesar, Cato, Pompey, or Venus were virtually unheard of for white people, but commonly held by the enslaved. These names were probably chosen by slaveholders to show off their education, or, as pretentious names given to purposefully debased people, they may have been intended as a dark irony. In another dehumanizing twist, classical names were also frequently given to dogs, horses, or ships of the era.

By Julia Preston