, Becky

Birth

Death

First Name

Person Biography

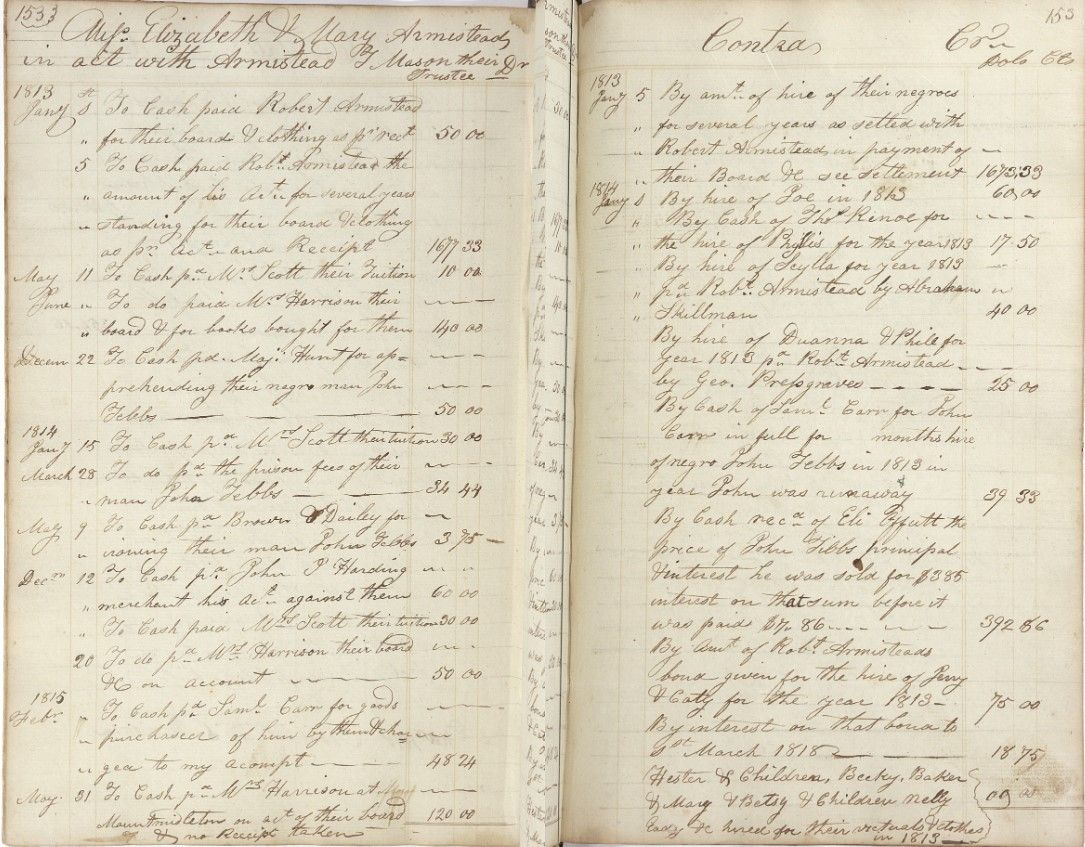

Becky was an enslaved woman on the Masons’ Raspberry Plain plantation in Loudoun County. She was listed in the Mason family manuscript account book as a person leased out to Robert Armistead in 1813 and to Stephen Ball in 1815 and 1816. Becky and her son Simpson were listed in Armistead T. Mason’s estate inventory in 1819, after which there is no further record of either Becky or Simpson.

Childbearing women like Becky were a valuable asset and became an investment for slaveholders. After Congress outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, a demand in the domestic market developed for fertile enslaved women, which elevated the value of younger women and preadolescent enslaved females in the marketplace. As one historian of slavery in Loudoun County has noted, “Women were valued for their fecundity, and traders made projections based on an enslaved’s ‘future increase.’” For example, Becky and Simpson were valued together at $200 in Armistead T. Mason’s estate inventory. Because Becky had a son, she was considered a more valuable asset than childless enslaved women. Slaveholders and traders often calculated the value of women and children as they would evaluate cattle and livestock, referring to children as “increase” and to older women as “breeders” past childbearing years. At first, mothers and children were sold together, but as prices and demand for younger enslaved people increased, slave traders began to sell mothers and children separately.

The laws of Virginia and other slave states mandated that any child born to an enslaved woman became the property of the mother’s enslaver. As a result, many slaveholders forced sexual relationships among enslaved men and women to increase the number of children born. The mortality of enslaved children was very high, so mothers often named their children only once a baby had survived more than a few days. Girls were often named after their grandmother, and boys were often named after their father, though owners sometimes called their enslaved workers by names other than those chosen by their mothers. Overall, the enslaved mother’s ability to make decisions regarding her children was very limited. Armistead T. Mason’s death further proved Becky’s lack of agency because his death meant a division of assets, which in turn meant the division of enslaved families. In life and death, slaveholders dictated where Becky and Simpson would go, separated or together.

By Rachel Birch