, Hester

Birth

Death

First Name

Person Biography

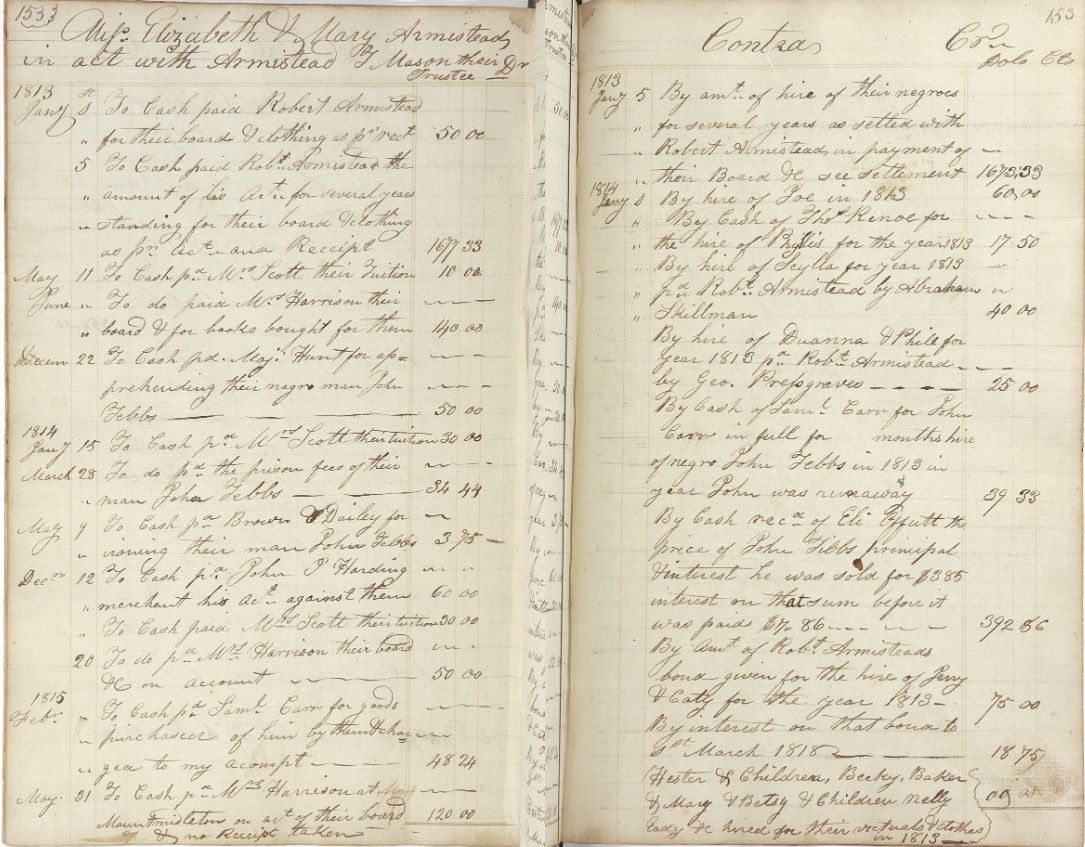

Hester, also known as Esther, was an enslaved woman held in bondage by Armistead T. Mason in trust for his underage cousins, Elizabeth and Mary Armistead. Hester was originally the property of the Armistead girls’ mother, Lucinda Ellzey Armistead. After Lucinda’s death, her husband Robert Armistead arranged for Armistead T. Mason to take over the property Lucinda had brought into their marriage. The 1805 deed of trust that established Mason as trustee also names Hester’s children, listing the “slaves which I acquired by my said wife or which has descended from those…by name of John Esther and her eight children namely Phanny Joe Lella Duanna Phillis Phill Frankey and Becca.” The listing of Hester and her children alongside John might imply a marriage or other family grouping, but with no other information about who John was, this is uncertain.

The account books and the 1805 deed of trust provide limited details about Hester, her life, and her family. She had at least eight children—by 1813, when she is first listed in the account book, given what historians have learned about childbearing among enslaved women, she may have had more. Enslaved women, on average, gave birth for the first time at age nineteen, two years earlier than the average for white contemporaries, and would typically have a child every two and a half years until the end of their childbearing years. Though slaveholders viewed babies and childbearing women as valuable property, frequent pregnancies combined with forced labor and poor living conditions negatively affected many women’s and children’s health and shortened their lifespans. After completing the agricultural and domestic work demanded by their owners, enslaved mothers also had to care for their own children and housekeeping tasks at the end of the day.

Hester’s life was further complicated by the system of hiring out enslaved labor, increasingly common in Virginia as the nineteenth century progressed. This system enabled slaveholders to gain income even if they had no current use for a particular person’s labor. The Mason family manuscript account book documents “Hester and her children” being hired out to work over a period of years, and notes that they were hired out “for victuals and clothes.” This indicates that the people who leased Hester and her family did not actually pay the Armistead trust, but instead only covered the cost of Hester and the children’s upkeep. Hiring out mothers and families was especially common when the legal owners were minors like the Armistead girls. As trustee, Armistead T. Mason probably wanted to avoid the expense of providing for young children.

Enslaved children could be hired out separately as young as nine years old, though sometimes they were allowed to remain with their mothers a few years longer. Hester and her children were usually hired out along with other enslaved people from the Armistead trust, including other women and children. This experience of leasing would have created uncertainty, not only about how they would be treated by whomever hired them year-to-year, but whether they would work with people they already knew.

In 1816, the account book records Hester’s death. No record has come to light revealing the fate of her children, or the extent to which they remained together or near each other after the Armistead sisters came of age and got control of their estate.

By Julia Preston