Williams, Richard

Birth

Death

First Name

Last Name

PersonID

Name in Index

Person Biography

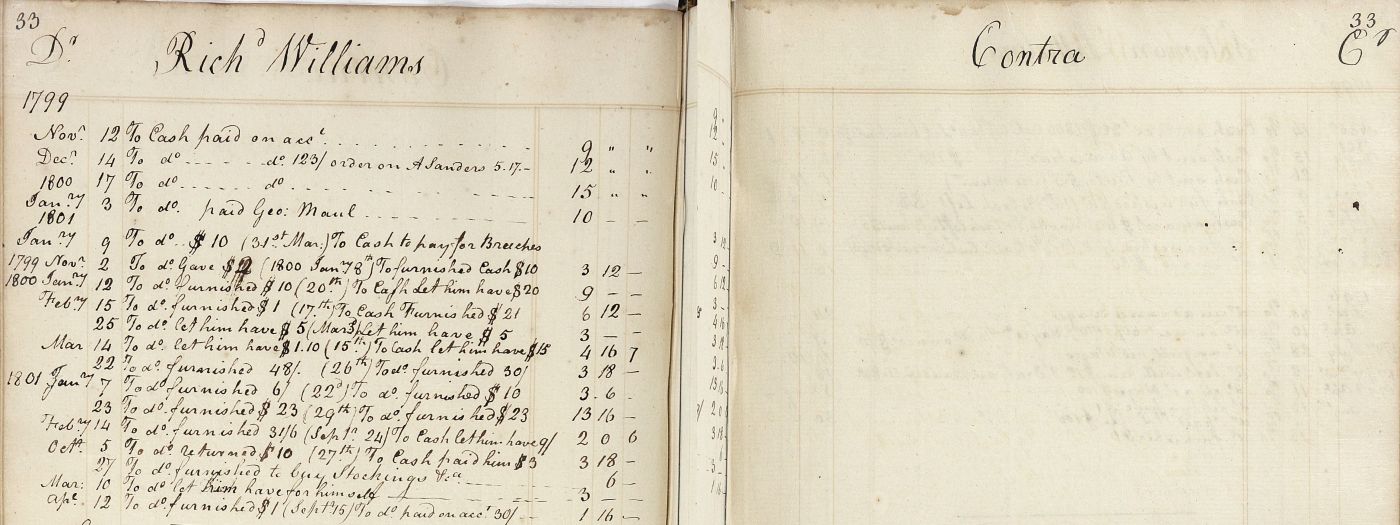

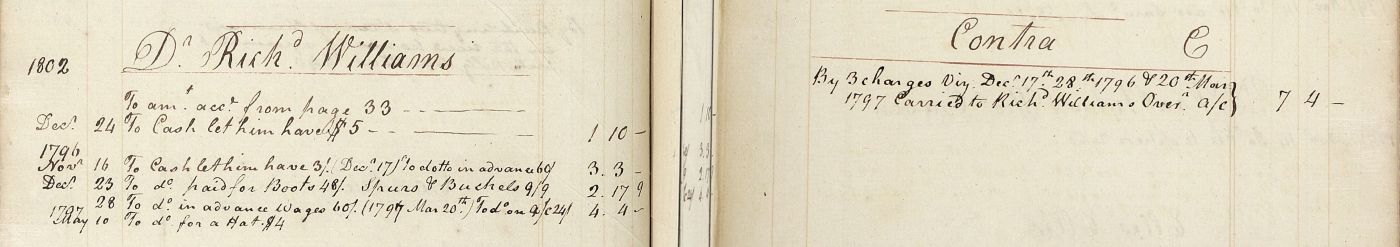

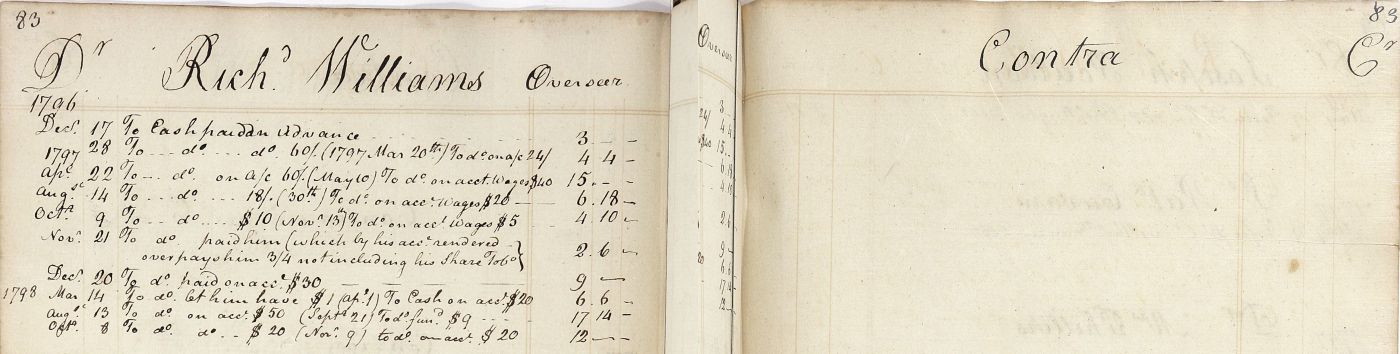

Richard Williams was an enslaved man who worked and dwelt at Stevens Thomson Mason’s Raspberry Plain estate in Loudoun County. Beginning as early as December 1796, Williams served as an overseer at Raspberry Plain, earning regular wages and a share in the profits from the farm. By 1798, it appears that Williams had become a member of Mason’s house staff, as Mason started outfitting him with finer clothing. When Mason traveled to Philadelphia in December 1798 to serve in the United States Senate, Williams accompanied him as a personal servant.

On 8 December 1800, Mason emancipated Williams for “faithful services and a strong attachment to [Mason’s] personal interest,” as well as for possessing “honesty, integrity, gratitude, honor and other estimable qualities that would ornament and give true dignity to any condition in society.” Williams spent his first five years of freedom at Raspberry Plain. After Stevens T. Mason’s death, Williams received money from the estate in 1804 in order “to equip himself for Kentucky.” While there is no documentation to show that Williams actually undertook the journey, the lack of historical records about him between 1805 and 1812 may indicate that he temporarily left Virginia.

On 1 May 1812, Williams received an additional $264.25 from the Stevens T. Mason estate. In 1815, Williams was able to use that money—in addition to other funds that he had earned since his emancipation—to purchase the freedom of his son, Evan Williams. Virginia law required that ex-slaves leave the state within 12 months of their emancipation, which prompted Mary Mason, Armistead T. Mason, and Charles P. Nett to petition the General Assembly for an exception on behalf of Evan Williams. The petitioners argued that “Richard Williams is now advanced in years and is becoming infirm, and that it would be a great comfort to him to have his son near him in the decline of life.” On 12 December 1815, the Courts of Justice approved their petition, which allowed Evan to remain with his father in Loudoun County.

While the Masons recorded very little about Williams’s employment from 1800 through 1815, he performed a variety of tasks on their behalf between 1816 and 1818. Of particular interest, Williams assisted Armistead T. Mason in the 1816 sale of two enslaved men—Ajack and Isaac—who belonged to the General Hugh Douglas estate. Mason’s records indicate that Isaac had tried unsuccessfully to escape prior to being sold, meaning that Williams played a minor—though complicit—role in keeping two other men enslaved.

Williams died no earlier than March 1825. Aside from his son, Evan, there is little historical evidence regarding a wife or other children, though there are several enslaved individuals with the surname of Williams who were included in Mary Mason’s estate.

By David Armstrong