Mason, Mary Elizabeth

Birth

Death

First Name

Middle Name

Last Name

Person Title

Maiden Name

PersonID

Note

Name in Index

Person Biography

Mary Elizabeth Armistead Mason (known as “Polly”) was born in Louisa County, in central Virginia, on 1 May 1760 to Robert Armistead and Mary Westwood. She was born at her father’s estate, Serenity Hall. The Armisteads had deep roots in Virginia, having first arrived in the mid-seventeenth century after the king granted their ancestor land in Elizabeth City County and Gloucester County, both located in the eastern part of the colony.

Mary Armistead grew up at Serenity Hall among the society of rich, white planters. “Polly” was renowned as a great beauty and belle. From her portrait—since lost—family tradition described her as “proudly conscious of her charms.”

Most girls in eighteenth-century elite Virginia families were educated at home, learning a combination of polite accomplishments and practical skills that prepared them for society, domestic life, and motherhood. Armistead would have learned through the example of her mother how to manage a plantation household. Although neither the estate nor her father were among the richest in Virginia, she married the wealthy Stevens Thomson Mason of Raspberry Plain on 1 May 1783. He was one of the one hundred richest men in Virginia, with land holdings in Loudoun and Stafford counties and in Richmond, the new state capital. During their twenty-year marriage, the couple had six children together.

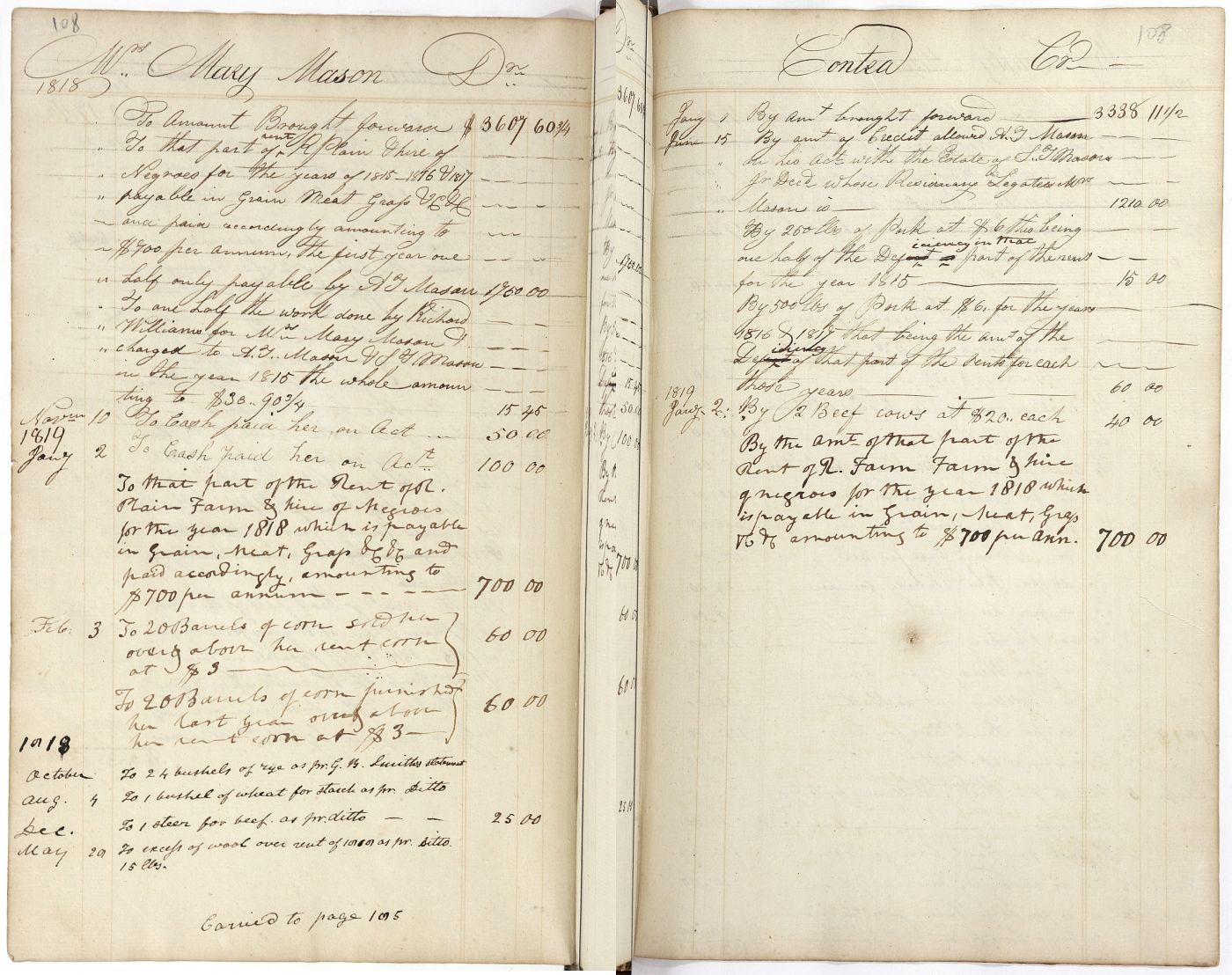

Mary Elizabeth Mason’s life changed dramatically as she entered widowhood when Stevens T. Mason died in 1803. She inherited portions of Raspberry Plain from her husband, as well as a variety of tools and sixteen enslaved people, which he listed by name in his will: “Billy and his wife Bett with all her Children and Grand Children Isaac, Tom, Gilbert, Lilly, Parthena, Latitia, Willson, Mary (the daughter of Winny), Barney, Syphax, Grace Fanny and her two Younger Children and Lucy.” Like many widows, Mary Mason often rented out her enslaved people to generate income.

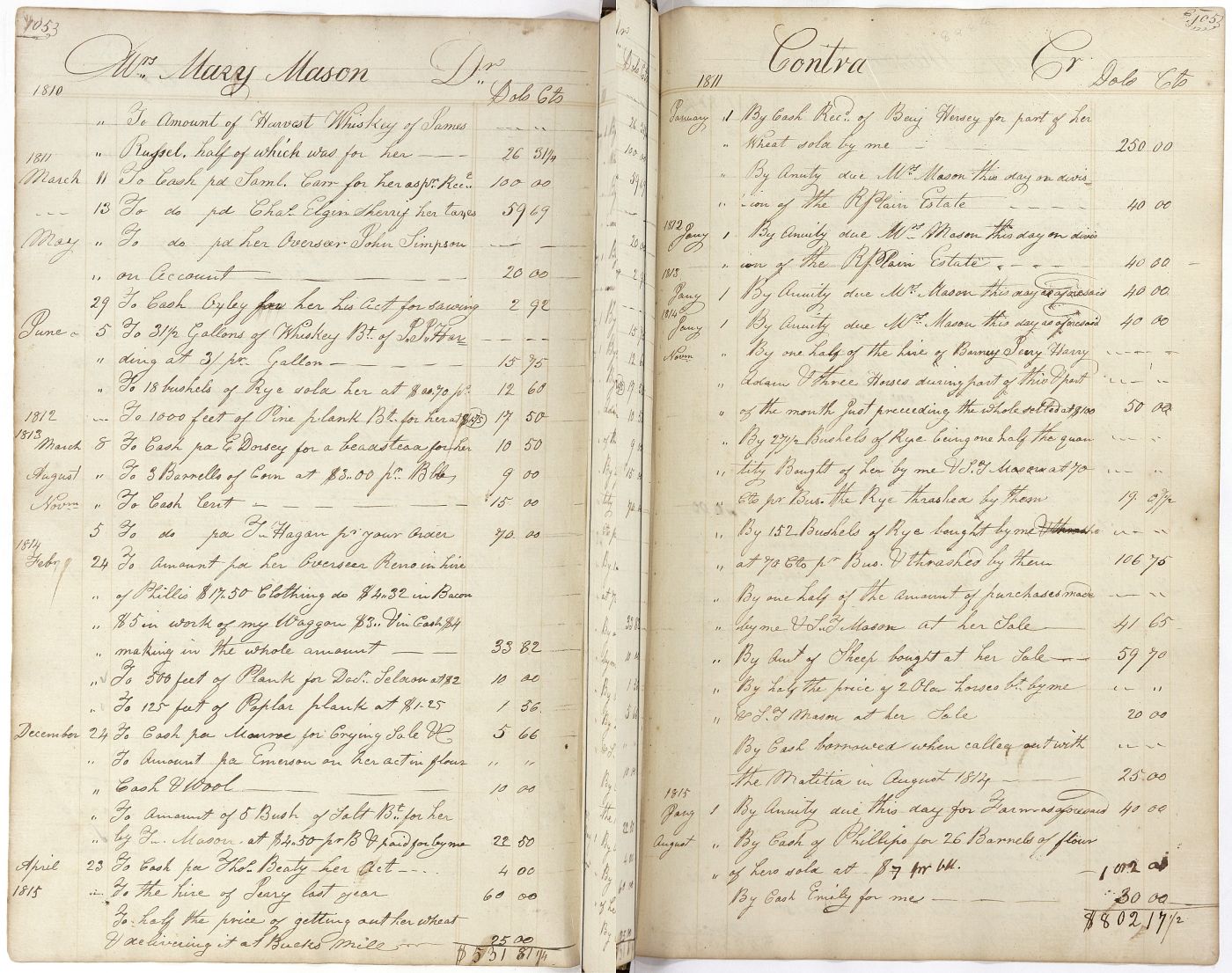

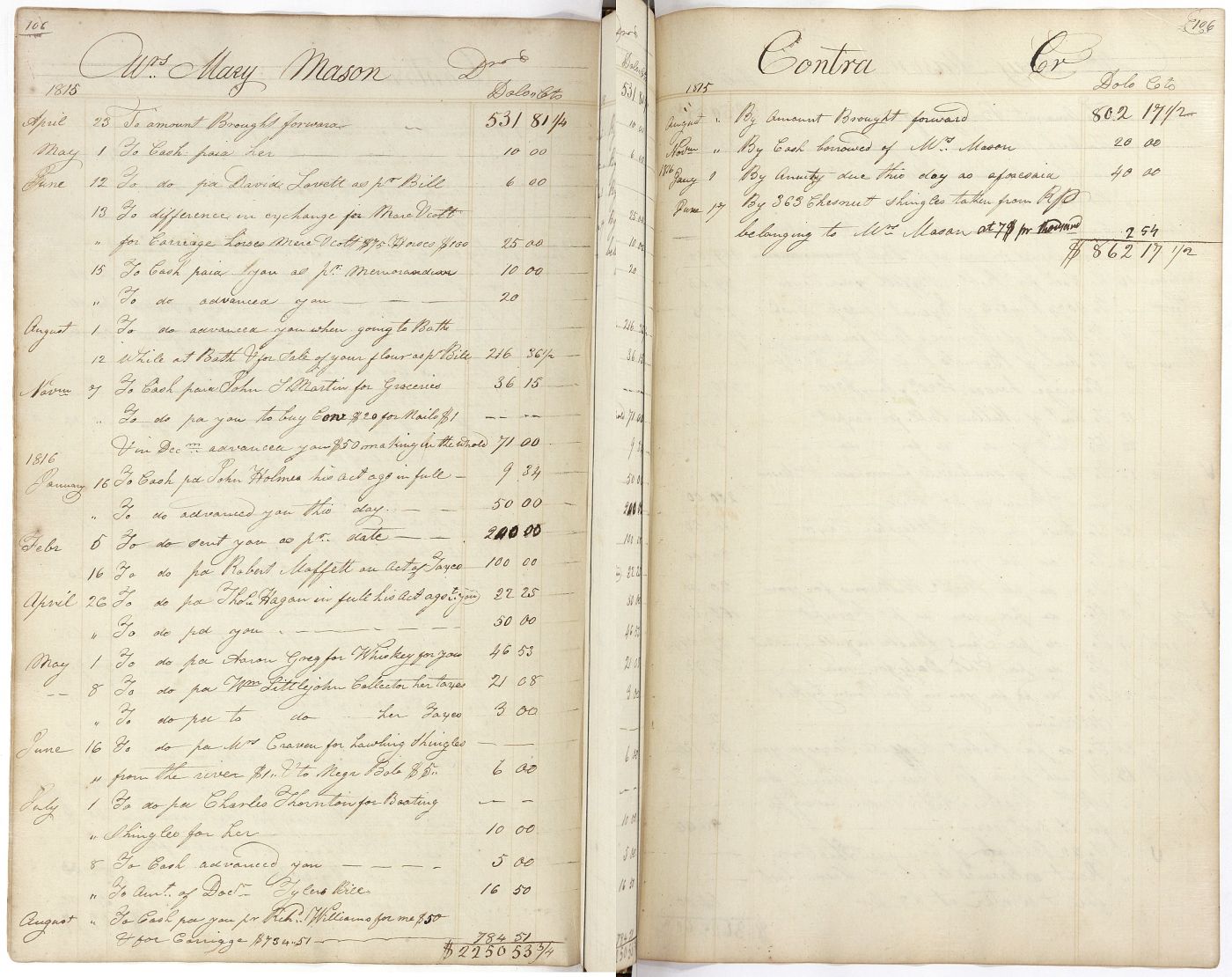

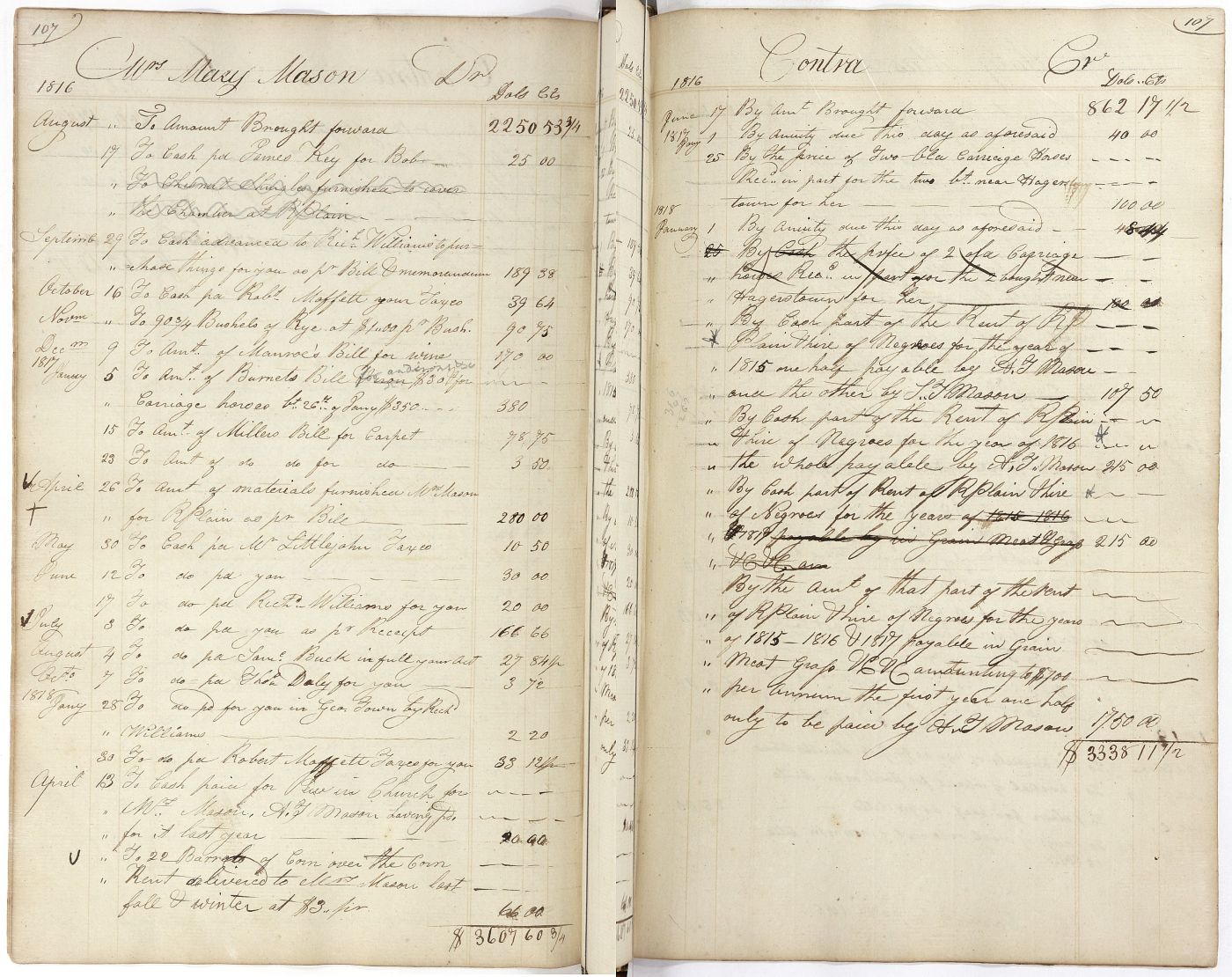

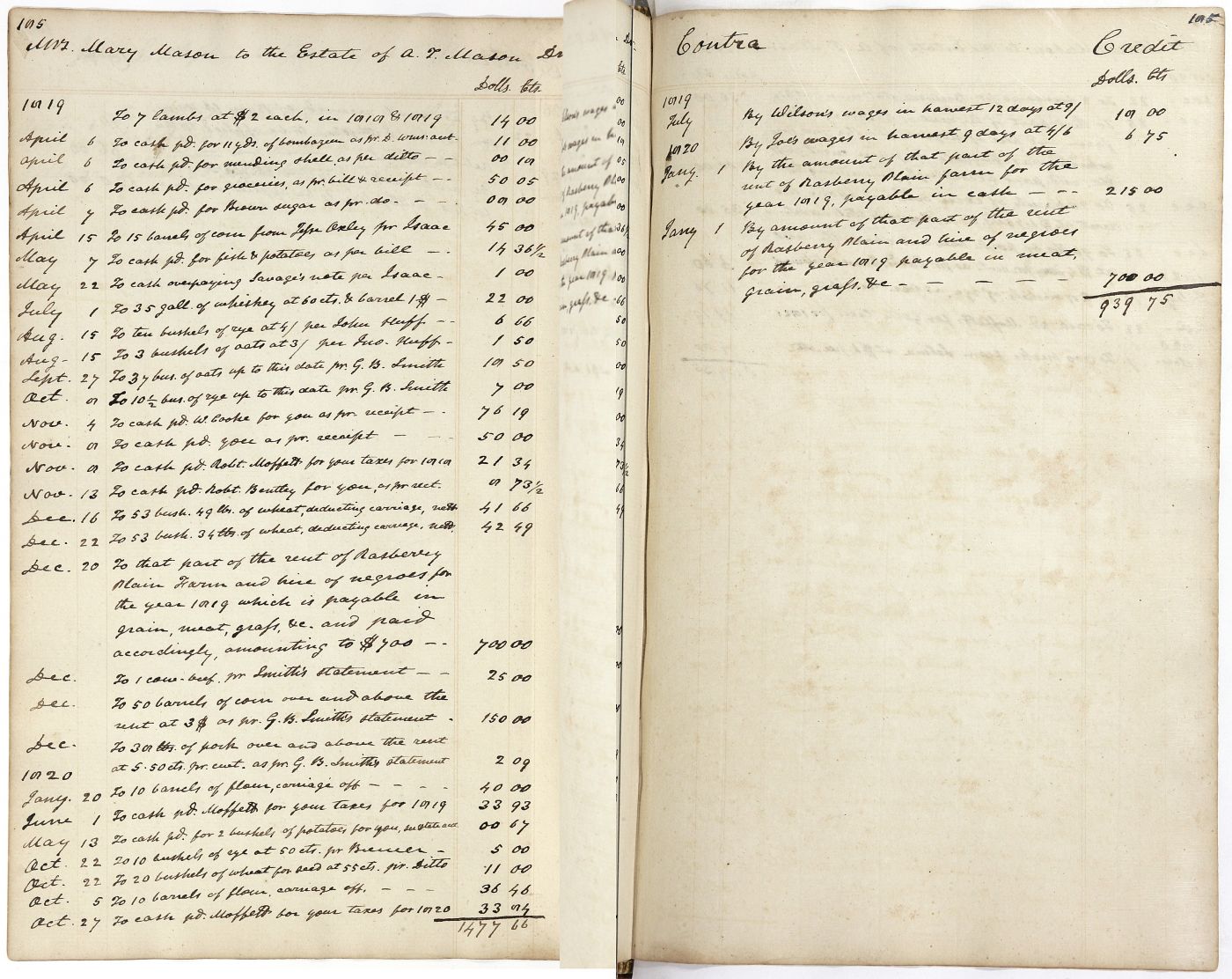

During her time as a widow, Mary Mason appears in the Mason family manuscript account book numerous times. The account book shows that she paid taxes and hired an overseer for her property, among more common purchases. She acted similarly to how other contemporary landed widows behaved and managed their properties following their husbands’ deaths. Because women often married men who were older than they were, widowhood was not uncommon, and this change in status often required women to assume their deceased husbands’ responsibilities as parents, business owners, and slaveholders. Widowhood also allowed women to escape coverture, meaning they were no longer legally tied directly to or controlled by a husband. Unlike wives, widows could control property, make business transactions, and enter spaces and buildings that were traditionally reserved for men, such as banks.

Mary Mason did not remarry. Remarriage after widowhood was more typical for younger widows, those with small children, or those with no children. Mason, who was in her forties with adult children when her husband died, probably did not feel the need to remarry.

By 1824, Mason was in her mid-sixties and understood that her health was deteriorating, so she penned her own will, which provided for the sale of her property and the division of her remaining wealth among her living children and grandchildren. In one notable section, she admonished one of her enslaved women, writing, “If Fanny Jackson refuses to go to my daughter in law EB Mason, she is to be put in the general stock of slaves to be sold with the rest of my ungrateful slaves.” Mason’s words show that she did not think kindly of most of her enslaved people. Mary Elizabeth Mason died at Raspberry Plain in 1825.

by Dierdre Gottert, Nina Erickson, and Cecilia Ward